Smart Calf Rearing Conf.: Unlocking the power of colostrum – new research challenges old rules

University of Guelph’s Dr. Michael Steele shows colostrum does more than protect newborn calves — it programs their physiology for stronger growth, resilience and milk yield

Editor's note: From September 25 to 27, the international Smart Calf Rearing Conference took place at the University of Madison in Madison, Wisconsin. Organized by Förster-Technik, Trouw Nutrition, the University of Guelph and the University of Wisconsin – Madison, the conference brought together 245 participants from around the globe to discuss the latest findings in calf physiology, health, housing and welfare, and 18 renowned speakers shared their expertise and research insights. Participants also had the opportunity to visit the university’s calf barn, where innovative solutions for calf rearing were showcased – including the CalfRailfeeding system for individual housing, developed by Förster-Technik.

For Dr. Michael Steele, professor of animal biosciences at the University of Guelph, the first feeding of a dairy calf is not just a management routine – it’s a biological turning point. He argues that colostrum is the most critical determinant of lifetime productivity and resilience. And despite decades of research, Steele believes the industry has only begun to uncover its potential.

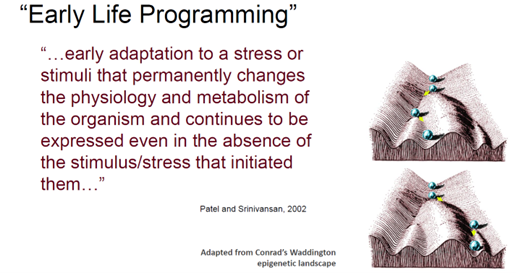

“What our lab studies is nutritional programming. We think of every single calf as a ball rolling down a hill,” he explained. “With nutritional interventions, even with colostrum feeding or milk feeding, we can affect the future phenotype of these animals.”

The idea that early nutrition can permanently shape physiology is driving a new wave of research into colostrum or the “liquid gold” of calf rearing.

Redefining what we know about colostrum

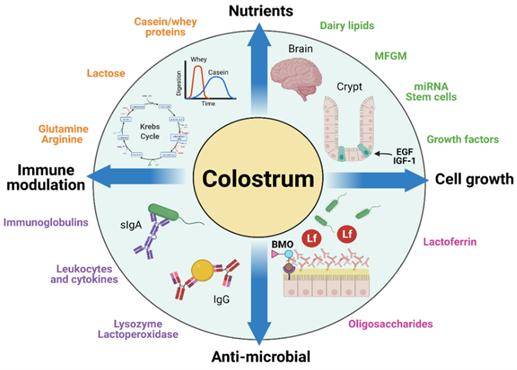

Steele’s research team focuses not only on immunoglobulins (IgG) but also on the vast array of other compounds in colostrum: insulin, growth factors, fats and oligosaccharides. He describes these as a biochemical orchestra still only partly understood.

The complexity of colostrogenesis, or the process of forming colostrum, still surprises even seasoned lactation scientists.

“There’s not even a consistent definition,” Steele said. “No one really knows when it occurs.”

His lab is mapping how nutrients, hormones and blood flow change in the mammary gland from 35 days before calving through the first week after birth. They’re discovering that dramatic shifts in structure and activity happen in the last seven days before calving.

His team’s research shows a burst of mammary-cell growth and a wave of apoptosis (cell turnover) around calving, offering evidence that the gland rapidly remodels to prepare for colostrum synthesis. Using ultrasound, Steele’s group is now measuring mammary blood flow and nutrient uptake in unprecedented detail.

“I think blood flow is really critical, and it allows us to look at uptake of different bioactives in greater detail,” he said. “Preliminary work suggested that cows produce less colostrum when the mammary glands are metabolically active right at dry-off.”

The finding suggests that management decisions weeks before calving, rather than hours, can influence colostrum yield and quality.

Challenging “colostrum basics”

Steele argues the bar for colostrum quality and feeding volume should be raised.

“Some of these colostrum basics that we talk about should be updated. I’m questioning our quality. We are at 22 grams per liter, and I think we should probably go to 25 grams per liter. We’re at about 50 grams per liter IgG – let’s go to 70. That is possible,” he said. “We have herds that are producing over 100 grams per liter IgG on average for their colostrum.”

He similarly recommends increasing feeding rate. The traditional 10% of body weight within 12 hours could be safely pushed to 12% (8% in the first meal of life and 4% in the second meal of life at 12 hours). Steele points to research showing calves that consumed 4 liters instead of 2 liters in their first feeding had higher daily gains and produced more milk in their second lactation, indicating evidence of long-term metabolic programming.

On-farm evaluation tools also deserve scrutiny, Steele said. Serum total protein (STP) has been a convenient proxy for IgG uptake and assessing passive transfer, but its reliability drops when farms use colostrum replacers.

“It is accurate if you’re feeding maternal colostrum, but not with colostrum replacer,” he cautioned. “So, you’re going to have to go straight to IgG, we should not be using STP to approximate this. It’s not accurate.”

Timing matters as much as the test. Sampling on day 4 to 7, he warned, can give a false picture because IgG peaks within 24–48 hours and then declines.

“The ideal time to test is 24 to 48 hours after the last meal of colostrum,” he said.

Practical, data-driven adjustments like these could sharpen how farmers monitor passive transfer.

Tube feeding works

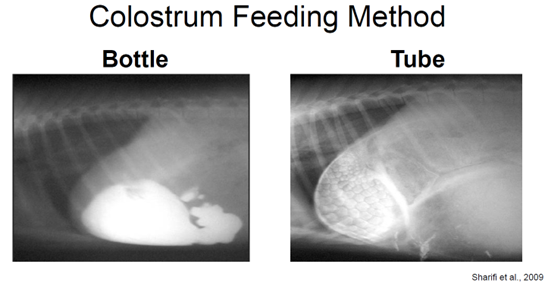

Steele’s first colostrum experiment tackled one of the industry’s most contentious questions – bottle versus tube feeding. Working with Alberta producers, his team compared IgG absorption after feeding 3 liters of quality colostrum through both methods.

“The producers asked me to do this study,” he recalled. “Personally, after conducting this study and seeing the data, I’m OK with tubing. I wasn’t OK with tubing before, but this is why we use science to break down biases.”

The results showed no difference in IgG levels between bottle- and tube-fed calves. Even though tube-fed colostrum enters the rumen first, acetaminophen-marker tests showed it reaches the abomasum (stomach) quickly and is absorbed efficiently. For large herds, Steele now considers tubing a safe, time-saving alternative when performed correctly.

Finding the “sweet spot” for volume and frequency

How much colostrum should a newborn receive in that crucial first feeding? Steele collaborated with researcher Sabita Mann to test 6%, 8%, 10% and 12% of birth-weight meals using colostrum exceeding 70 g/L IgG. The data pointed clearly to an optimal midpoint.

“About 8-10% looks like a pretty good ‘sweet spot’ with respect to IgG in the first meal,” he said. “I have no concerns with 8-10% based on this data for the first meal, but we need to know more about the second meal volume which is rarely studied.”

While higher volumes might cause abomasal backflow, the 8-10% rate achieved strong IgG levels without adverse effects. He remains cautious about the widely used “apparent efficiency of absorption” (AEA) calculation, calling it “flawed” because un-labeled IgG prevents researchers from knowing exactly how much enters circulation. However, he says it’s still the best measure available.

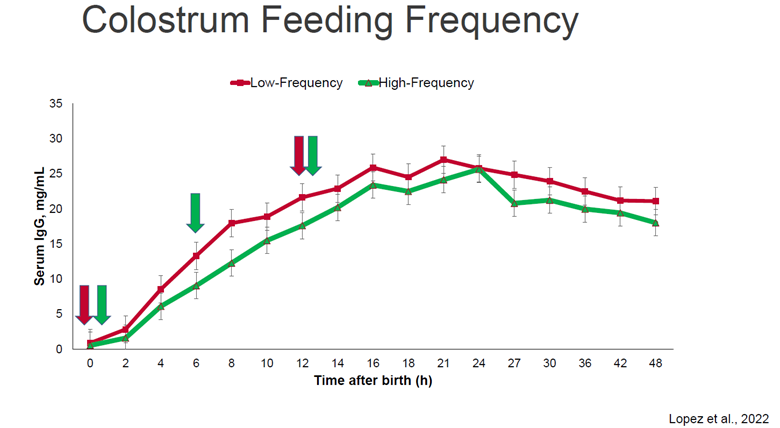

Another question Steele’s group addressed is feeding frequency. PhD student Alberto Lopez compared calves fed two large colostrum meals (8% + 4% body weight) versus three smaller ones (4% + 4% + 4% body weight). Despite higher early IgG after the big meal, total absorption ended up the same.

“The gut is quite open even at six and 12 hours,” Steele said. “So, from a labor standpoint one big meal followed by a second meal can work.”

This finding gives producers flexibility: a timely second feeding matters, but extra sessions don’t appear to boost immunity.

Colostrum quality and enrichment

To test whether enriching low-quality colostrum is worthwhile, Steele’s lab compared feedings of 30, 60, and 90 g/L IgG colostrum. Surprisingly, IgG absorption rose linearly and without signs of saturation, suggesting calves can handle far higher IgG loads than commonly assumed.

Supplementing 30 g/L maternal colostrum with a dried colostrum replacer boosted blood IgG levels, confirming enrichment’s potential for low-quality batches. However, raising 60 to 90 g/L showed no statistical increase.

“The strategy may help poorer-quality colostrum,” Steele said. “But we still need to look at other components like fats, oligosaccharides and health outcomes to know the full picture.”

Lessons from the beef side

Steele often looks beyond dairy herds to beef herds for insight. When PhD student Koryn Hare milked 75 Angus cows pre- and post-calving, calves that suckled directly or received bottled colostrum showed no difference in IgG levels. More strikingly, beef cows on higher-energy diets produced more IgG. Yet their calves’ serum concentrations remained well below dairy standards – averaging 24 g/L instead of the dairy target of 10 g/L or more.

“If you look at what Sabina Mann’s meal-size data showed, it’s pretty darn close to this. So, it is possible in dairy. But I think the amount that we feed them is very low compared to what would happen in nature,” he said. “In the beef world, most of the calves’ first meal is 500 grams of IgG.”

It is estimated that some beef calves even reach 1,000 grams of IgG intake in the first 24 hours of life while dairy calves typically get 200 grams which is a gap Steele says is hard to ignore. He suggests reevaluating volume limits and developing practical ways to deliver higher IgG mass without overfilling the abomasum.

The overlooked power of transition milk

For all the focus on the first feeding, Steele is equally intrigued by what happens afterward. He calls transition milk, or the second to fifth milking, “a forgotten gold mine.”

“Our second milking is still high in IgG and protein,” he said. “So why would we ever get rid of that?”

His studies show transition milk differs sharply from mature milk in protein, fat and fatty-acid profile. It contains roughly half the lactose but far more oligosaccharides, which are complex sugars that nourish beneficial gut microbes and may even enhance IgG absorption.

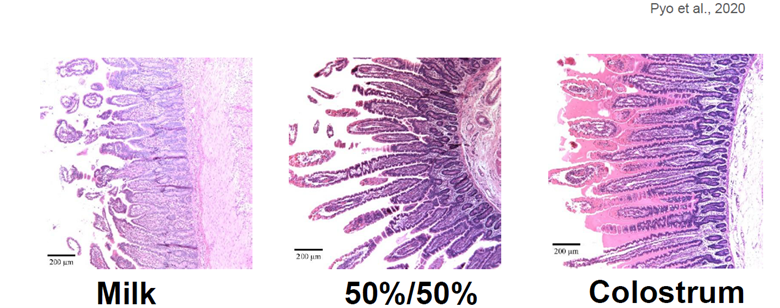

In experiments where calves received a 50/50 mix of milk and colostrum as their second meal, intestinal development improved markedly: taller villi and thicker mucosa signaled better nutrient uptake. IgG levels also declined more slowly over the first week, suggesting extended colostrum feeding helps “spare” antibodies in circulation.

Extended colostrum feeding boosts health, survival

Working with veterinarian Dr. David Renaud, Steele tested whether colostrum-based diets beyond day one could strengthen calves through weaning. In a study with 200 Holstein heifers and three treatment programs:

- transition – gradual mix of milk and colostrum

- extended – 10% colostrum replacer added for 14 days

- combined program

All three outperformed the control group that switched immediately to milk replacer.

“The odds of keeping them healthy earlier in life were better in all three treatments compared to the control,” Steele said. “The odds of survival were greater, and this was during a Salmonella Dublin outbreak.”

The results reinforce that the benefits of colostrum don’t end after the first feeding. Bioactive compounds may continue supporting gut integrity and immune response well into the second week of life.

Colostrum as a strategic therapeutic tool

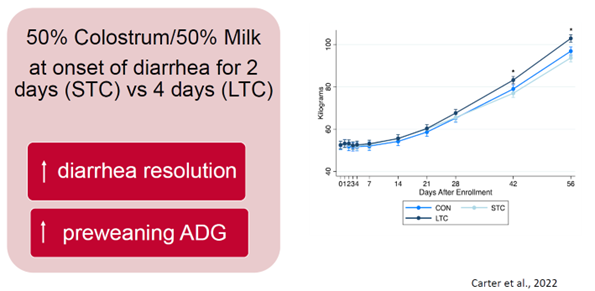

Steele’s team also tested colostrum as a treatment, not just a preventive. On a commercial dairy-beef farm plagued by calf diarrhea, they fed scouring calves a 50/50 colostrum-milk mix for either two or four days.

“It resolved the diarrhea faster in the group that was fed this mixture for four days compared to two and also the control,” he said. “They ended up growing more too, which I find intriguing.”

The mix worked best, showing how strategic use can enhance recovery while supporting growth. Steele notes that some progressive farms have already adopted the practice.

The future of calf feeding

Steele’s research team is now integrating automated feeders that monitor drinking speed and intake drops to identify early signs of illness. Feeding tailored colostrum supplements to those calves may soon be possible in what Steele calls “individualized calf feeding.”

Steele envisions a future where every calf receives a data-driven colostrum program matched to its needs that include volume, frequency and composition optimized through sensors and smart feeders.

“We’re going to be feeding animals on an individual basis,” he predicted. “You’re seeing this in piglets all the time, and we can use some of these technologies to make these mitigation strategies a lot stronger.”

For now, he encourages dairy producers to focus on fundamentals like quality, quantity, quickness and cleanliness all while embracing new evidence that challenges tradition. Better colostrum management, he said, is the surest investment in a herd’s genetic and economic future.

Key takeaways

- Aim higher on quality. Target ≥ 25 Brix and ≥ 70 g/L IgG; exceptional herds exceed 100 g/L

- Feed enough, fast. Deliver about 8-10% of body weight within one hour of birth; follow with a timely second meal

- Monitor smartly. Use STP only for maternal colostrum and sample 24 to 48 hours post-feeding

- Don’t fear the tube. Proper tubing achieves IgG transfer equal to bottle feeding

- Use transition milk. Second and third milkings still carry immune and growth factors; don’t discard them

- Consider extended or therapeutic use if needed. Blended colostrum can aid recovery from diarrhea and improve post-weaning performance

Colostrum is far more than an immune boost; it’s a biological signal that programs a calf’s future. While many questions remain about oligosaccharides and fats and how exactly the mammary gland controls their synthesis, his message to farmers and nutritionists is clear: the more precisely we manage colostrum today, the stronger and more resilient our herds will be over the long-term.