Smart Calf Rearing Conf. - Measuring what matters: A new way to benchmark dairy calf health

A new benchmarking model helps farmers target diseases that matter most

Editor's note: From September 25 to 27, the international Smart Calf Rearing Conference took place at the University of Madison in Madison, Wisconsin. Organized by Förster-Technik, Trouw Nutrition, the University of Guelph and the University of Wisconsin – Madison, the conference brought together 245 participants from around the globe to discuss the latest findings in calf physiology, health, housing and welfare, and 18 renowned speakers shared their expertise and research insights. Participants also had the opportunity to visit the university’s calf barn, where innovative solutions for calf rearing were showcased – including the CalfRail feeding system for individual housing, developed by Förster-Technik.

When it comes to raising healthy calves, dairy producers often face a familiar challenge: how to evaluate herd health when “everything seems as usual.” Subtle but persistent disease patterns can quietly erode calf performance, making it difficult to pinpoint where to focus efforts.

Dr. Sébastien Buczinski, assistant professor at the University of Montreal, spoke recently at the Smart Calf Rearing Conference. He believes benchmarking can provide the motivation and clarity needed to drive improvement in dairy calf health and wellness.

“I'm a veterinarian, working in an ambulatory clinic at the University of Montreal,” Buczinski explained. “We provide services to small dairy farms that are relatively close to the university. Our average herd size is 80 cows, and we talk to producers about their calves. Some of them are doing nothing to improve, so we try to think about ways for them to improve and consider how we can motivate them to change. We find that one of the best ways to motivate change is to compare producers with the neighbors.”

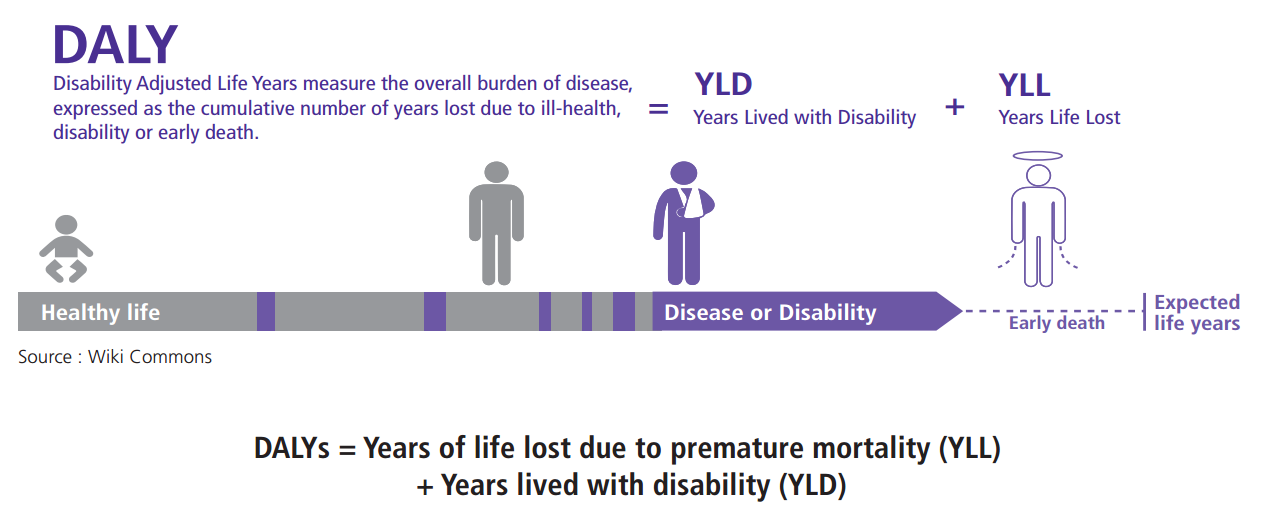

This concept of comparing performance against peers, or benchmarking, is already common for growth and production traits. Buczinski and his team have applied it to calf health, adapting a population-health framework from human medicine: the Disability Adjusted Life Year (DALY). Originally developed by the World Health Organization to compare disease burden across countries, the DALY combines two key components – years lived with disability and years of life lost due to premature death – into a single metric.

“We all have different origins and a lot of different diseases and disorders,” he said. “This was the concept of the DALY, and it's a common metric to be able to compare different countries and populations.”

By adapting the DALY framework to dairy herds, Buczinski’s team aimed to give veterinarians and farmers a tool to quantify the impact of calf diseases on health and productivity in a standardized way. Instead of looking at prevalence numbers in isolation, the DALY approach weights diseases by their severity and combines them into a single indicator that can be compared between farms.

Transitioning from human health to calf health

The project focused on pre-weaned dairy calves and was conducted on 40 dairy farms near the Bovine Ambulatory Clinic in Sainte-Hyacinthe, Quebec. The research had three primary objectives:

1. Develop a structured way to assess health and quality of life during a farm visit assessment

2. Determine the impact of a disease: disability weights (DW)

3. Report standardized DALY values for pre-weaned calves across farms

To develop the disability weights, Buczinski’s team consulted both veterinarians and producers to capture different perspectives. They focused on key diseases such as diarrhea, respiratory disease, umbilical infection, arthritis, inadequate transfer of passive immunity, fractures, would abscess, dystocia and congenital defects. This multi-stakeholder approach helped standardize the severity of diseases in real-world contexts.

“To have a good representation of the disease and its weight, you have to talk to different kinds of people who have a broad knowledge of the disease impact you are trying to distinguish,” he explained. “So that’s why we spoke to 39 Quebec producers and 52 veterinarians interested in calf health to see how they perceive these diseases.”

Interestingly, while most perceptions aligned closely between producers and veterinarians, there was one notable exception.

“Veterinarians perceive arthritis as having a much more severe impact to the calf than producers,” Buczinski said. “But when producers talk about arthritis, it's not always what a veterinarian would call arthritis.”

Measuring calf disease burden

Over the course of the study, the team assessed roughly 1,900 calves with a median age of 23 days. They conducted five farm visits, using a prevalence approach to collect disease data, complemented by mortality incidence data. Although many farms had digital herd health systems, usage was inconsistent.

“People have the system including 38 out of 40 farms, but most don't use it,” he noted. “So, we could not determine the correlation between what we observe and what the producers know, because a lot do not report health issues, even if they say they do. And I still use a paper notebook for recording systems.”

Despite these limitations, the data painted a clear picture. Median prevalence rates across farms were:

• Diarrhea: 28.6%

• Respiratory infection: 7.2%

• Umbilical infection: 5.1%

• Inadequate transfer of passive immunity (ITPI): 23.9%

Inadequate transfer of passive immunity remained a widespread issue, even in well-managed herds. Mortality was primarily driven by dystocia, followed by diarrhea and respiratory disease.

Importantly, when the team multiplied disease prevalence by disability weights, they were able to calculate years lived with disability per 10 calves, which was the first component of the DALY metric.

The results showed wide variation between farms. Some herds had relatively low overall disease burden but were dominated by one or two major issues, such as umbilical infections. Others had higher prevalence of diarrhea and respiratory disease, which accounted for most of the DALY values. On average, Buczinski reported 3.37 DALY per 10 calves – integrating both morbidity and mortality data.

Benchmarking as a motivational tool

The power of the DALY approach lies in its ability to turn dissimilar disease data into a single, comparable number that can motivate action. Buczinski often begins discussions with producers by showing them where their farm sits relative to others.

“When I'm presenting the results to producers, the first question most ask is where am I?” he said.

This simple benchmarking shows where a farm falls among 40 peers and often triggers constructive conversations. If respiratory disease contributes the majority of DALYs on a farm, for example, attention can focus on colostrum management, ventilation or vaccination protocols. If mortality is unusually high, calving management and neonatal care may be prioritized, according to Buczinski.

These insights are particularly useful for veterinarians and nutritionists, who are providing herd health services. Instead of relying solely on prevalence data, they can use DALY-based indicators to rank disease problems by their actual impact, and tailor recommendations accordingly.

Recording matters

The study also highlighted a major limitation in calf health monitoring: poor on-farm recording of disease events. Despite the availability of herd management software, fewer than one-quarter of producers in the study consistently recorded calf health information. This data gap made it impossible to use a true incidence-based DALY calculation, which would have provided even more detailed insights, according to Buczinski.

“The importance of recording and the value in recording data is a key for the evolution of the system but it’s a big challenge,” he observed.

The implication is clear: better recording enables better benchmarking, and better benchmarking leads to targeted health improvements. Providing meaningful feedback to producers is essential to closing this loop.

“What was positive at the end of this study is that if we want to implement this and have more data entered by the producers, we need to analyze the data and give them data-driven feedback that will help them make changes to their operation. We need to motivate farmers to record because they see the added value,” he concluded.

Implications for the dairy sector

For dairy producers, veterinarians and nutritionists, Buczinski’s work offers a new way to translate calf disease data into actionable priorities. The DALY framework provides several practical benefits:

- Simplified comparison: By reducing multiple diseases to a single metric, it becomes easier to compare herds and track progress over time.

- Prioritization: Identifying the diseases that contribute most to DALY values helps target interventions where they will have the greatest impact.

- Motivation: Benchmarking against peers can stimulate discussion and change, especially for farms lagging behind.

- Data-driven decisions: Integrating DALY metrics into herd health reviews encourages more consistent disease recording and analysis.

Perhaps most importantly, this approach bridges the gap between veterinary medicine, epidemiology and farm management. It gives all stakeholders – farmers, veterinarians, advisors – a common language to discuss calf health performance.

Buczinski’s study demonstrates that population health concepts from human medicine can be meaningfully adapted to livestock. While DALY calculations may sound complex, the principle is straightforward: measure the burden of disease in a way that allows comparison, prioritization and improvement.

The biggest barrier remains data recording on farms. Encouraging producers to document disease events consistently and providing them with useful benchmarking feedback will be critical to realizing the full potential of this method.

In an industry where early-life calf health has long-term consequences for productivity, reproduction and animal welfare, the ability to benchmark disease burden objectively represents a significant advance. By borrowing tools from public health, dairy professionals can sharpen their focus on the issues that matter most and drive meaningful improvements across herds.