Beef X Dairy Summit: Diagnostic trends highlight persistent and emerging disease risks in cattle

Iowa State diagnostician outlines persistent threats and emerging concerns facing calf health

Disease surveillance and diagnostic trends continue to underscore persistent vulnerabilities in U.S. beef and dairy systems, particularly as cattle sourcing patterns shift and new disease pressures emerge. That was the central message delivered by Dr. Drew Magstadt, clinical associate professor and veterinary diagnostician at the Iowa State University Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory, during a recent presentation at the Four Star Veterinary Service Beef-on-Dairy Summit held in Celina, Ohio. The Summit was attended by more than 300 beef-on-dairy producers from across the United States.

“We're going to talk about some diseases that are either happening in the cattle industry now or that we certainly hope don't happen,” Magstadt said.

From bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVD) to respiratory disease, scours, Salmonella Dublin and highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI), Magstadt emphasized that diagnostic data often reveal issues that vaccination programs and management practices may be failing to fully address.

BVD remains a persistent and evolving threat

Although bovine viral diarrhea virus has long been recognized by the cattle industry, Magstadt stressed that it remains a significant concern because of its ability to perpetuate itself through persistently infected (PI) animals.

“The big one, and why BVD continues to be an issue, is persistent infection,” he explained.

When a pregnant cow is infected during early gestation, the virus can cross the placenta and infect the fetus before its immune system develops.

“That fetus will recognize the virus as part of itself, and it will never ever mount an immune response to the virus,” Magstadt said. “That animal, if born alive, will shed virus every second of every day of its life.”

PI calves may survive to breeding age but will continuously expose herd mates to the virus and allow BVD to persist in cattle populations.

“This is really the way that BVD continues to be an issue is that we continue making PI calves that continue shedding virus to others,” he said.

Diagnostic testing has improved, and Magstadt highlighted the effectiveness of ear-notch testing using immunohistochemistry (IHC) or PCR.

“There are several tests available that are very good, and many labs can run this test,” he said.

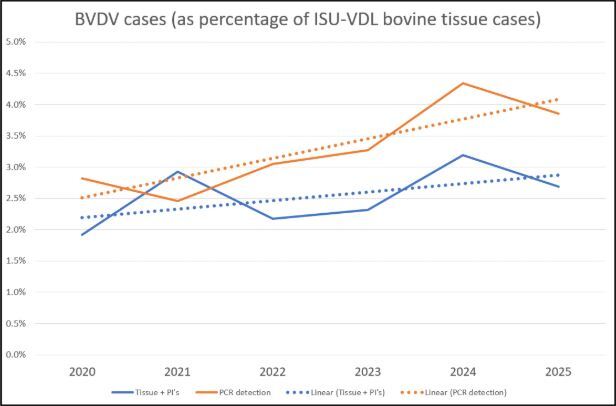

Recent diagnostic trends, however, are concerning.

“It certainly seems like BVD incidence is trending in the wrong direction,” Magstadt said, noting increases in PCR detections and tissue cases where BVD was suspected.

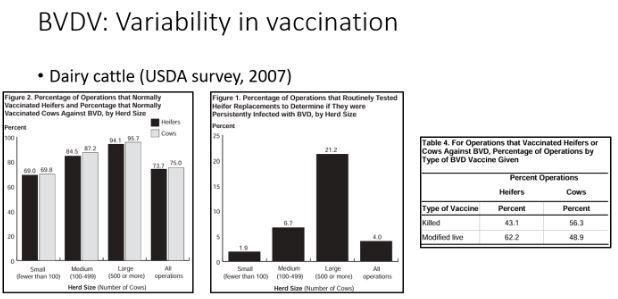

Vaccination practices may be part of the problem. Based on available survey data, Magstadt noted that only about 60% of beef operations vaccinate for BVD, and just 3.7% test for persistent infection. “

“It seems like we're utilizing vaccines to carry the day on this,” he said, “but at the same time, only 60% of beef cows are actually vaccinated.”

On the dairy side, testing rates are similarly low, and many operations rely heavily on killed vaccines.

“Killed vaccines are great for boosters,” Magstadt said, “but they might not be great for establishing a very good long-term immunity to BVD, particularly BVD that can get to the placenta and get to the fetus.”

Calf sourcing practices also influence risk.

“If you're single sourcing calves from all over the place, those are the situations where we run into issues,” he said, referencing recent outbreaks with high mortality linked to PI animals.

Scours: management matters as much as pathogens

Magstadt described scours as a multifactorial disease where management often outweighs the specific pathogen involved.

“We can't talk about calves without talking about scours,” he said.

However, diagnostic patterns vary by age.

“In the first week of life, the most common thing we diagnose is E. coli,” Magstadt said.

Between days 7 and 28, coronavirus, rotavirus and cryptosporidium become more common, while coccidiosis typically emerges after three weeks of age.

However, underlying management factors are often decisive.

“If you have a group of calves and none of them got colostrum, does it matter if the E. coli killed them or rotavirus killed them? No, it doesn't,” he said.

Colostrum intake, environmental hygiene, temperature stress and pathogen load all influence disease outcomes.

“Colostrum intake is massively important in preventing and the survivability of a disease outbreak of scours,” Magstadt said.

Rotavirus appears to be increasing in diagnostic submissions. He said around 25% of the cases that come in from a clinical case of enteric disease tend to be strongly positive for rotavirus. Increased sequencing requests may eventually support more tailored vaccination strategies, similar to approaches already used in swine production.

Respiratory disease driven by viral damage and stress

Respiratory disease in calves remains heavily influenced by viral pathogens that compromise the lung’s natural defenses.

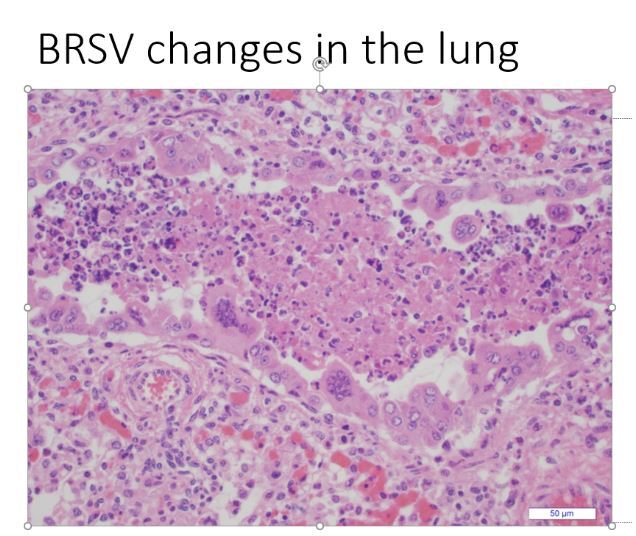

“Everything we're doing from an animal health standpoint when it comes to respiratory disease, we want that airway to look exactly like the image on the left,” Magstadt said, describing a healthy bronchial airway.

Viruses such as bovine respiratory syncytial virus (BRSV) damage the airway’s ability to clear debris and bacteria as seen on the right-hand side of the image above.

“That is not healthy and creates a situation where the calf is not able to respond to any kind of challenge,” he said.

BRSV is the most commonly diagnosed viral respiratory agent in young calves. Secondary bacterial infections often follow viral damage.

“The antibiotics aren't for the viruses,” he said. “The antibiotics are for the bacteria that get down in there.”

Environmental and management stressors compound disease risk.

“Stress, transportation and dehydration affect the mucus that gets secreted,” Magstadt said. “Any of the stresses that you can eliminate will make the animal better able to handle challenges that it faces every day on its own.”

Salmonella Dublin hits dairy and beef-on-dairy calves hardest

Salmonella Dublin represents one of the most severe disease challenges Magstadt described.

“It's a bear, isn't it?” he asked the audience.

Unlike enteric Salmonella, Salmonella Dublin causes septicemia.

“It's a septic bacteria, so it goes everywhere,” Magstadt said.

Clinical signs include fever, anorexia, respiratory distress and sudden death. The disease overwhelmingly affects dairy and beef-on-dairy cattle.

“About 95% to 98% of our Salmonella Dublin cases are dairy or beef on dairy,” Magstadt said, noting its rarity in beef calves.

Recent cases have appeared in older beef-on-dairy animals in feedlots, adding to concern. But diagnosis is usually straightforward.

“We can grow this organism from just about anything we send to our lab,” Magstadt said. “It is everywhere.”

HPAI reshapes disease response in dairy cattle

Highly pathogenic avian influenza created unprecedented challenges when it emerged in dairy cattle.

“HPAI made cows pretty sick,” Magstadt said. “The clinical signs included dramatic drops in feed intake and milk production, thickened colostrum and widespread illness. Infected operations were treating 15% of the dairy herd every day,” he said, describing large operations managing thousands of sick cows.

Bulk tank testing later revealed that virus circulation preceded clinical recognition.

“One site was positive in a bulk tank test 16 days before they knew they had an issue,” Magstadt said.

Cats proved to be an early warning signal.

“A lot of the dairies, all at one time, started reporting a sharp reduction in rodent control cats,” he said.

Cats consuming infected milk developed neurologic disease and died, prompting influenza testing.

Despite the severity in cows, calf outcomes have been more reassuring.

“They fed milk from infected cows to calves, and it caused some fairly mild disease,” Magstadt said.

More importantly, transmission between calves was not observed in research trials.

Pasteurization emerged as a key control tool.

“Pasteurization definitely works and massively decreases the load of actual live virus,” he noted.

Other emerging concerns: Asian longhorned tick and New World screwworm

In addition to more familiar pathogens, Magstadt cautioned that emerging diseases could pose serious challenges for calf health, labor demands and continuity of business.

One of those threats is Theileria orientalis, a tick-borne disease transmitted by the Asian longhorned tick.

“It hits red blood cells and causes anemia; it's a lot like anaplasmosis,” he said.

However, unlike anaplasmosis, Theileria can affect younger animals. Iowa has already confirmed multiple cases.

“On these animals, we saw a massive tick burden,” Magstadt added, noting that control is complicated by the tick’s ability to reproduce without mating.

“A female tick doesn't have to come across a male tick to reproduce. She can make about 3,000 clones of herself,” he explained.

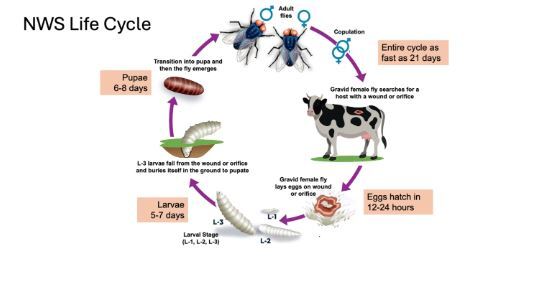

Even greater concern surrounds the potential reintroduction of New World screwworm, a parasitic fly larva eradicated from the US in the 1960s.

“This is not just a cattle issue,” Magstadt said. “It can infect is dogs, cats - basically anything that's warm-blooded, including humans.”

The parasite gains entry through wounds such as navels, castration sites, ear tags and dehorning wounds.

“The big issue with this is that they infect and feed on live tissue,” he said.

Source: USDA APHIS

Recent detections in Mexico suggest increasing risk. The most recent is just 70 to 120 miles south of the US border.

“It's becoming a big, big issue in southern Mexico,” Magstadt said, warning that if it reaches US cattle, producers could face significant labor demands and movement restrictions.

“A massive amount of labor would be needed to ID, treat and confirm that the animals are OK and to release a site from quarantine.”

Together, Magstadt concluded that these disease and diagnostic insights highlight the importance of surveillance, management fundamentals and biosecurity as beef and dairy production systems face both longstanding and emerging disease threats.