Conventional vs. Intensive Heifer Rearing: An Economical Comparison

Intensive heifer rearing may cost more per day, but per heifer, intensive methods stack up, according to a comparative study by three veterinarians.Dairy replacement heifers are often viewed as simply another cost-of-doing business on a dairy, write Veterinarians Michael Overton, Robert Corbett and W.Gene Bloomer.

While replacement heifer programs usually rank as the second largest cost of producing milk, usually trailing only feed costs, the expense associated with feeding and rearing heifers should be more properly viewed as an investment towards the future.

Much like any other investment, money is spent today for a return that will not be realized until the heifer calves and enters lactation, write the three experts.

Within the dairy heifer growing period, the highest daily expense is during the preweaning period and is a consequence of the liquid diet and the high labor costs associated with liquid feeding. As a result of the high up-front costs, many producers adopt management and feeding strategies that appear to save money up front, but result in greater opportunity costs in the future.

Conventional wisdom regarding the feeding of neonatal calves has been that one should slightly limit or restrict the caloric intake from the liquid diet in an effort to stimulate consumption of calf starter. The belief is that hungry calves will begin consuming starter grain earlier and in larger amounts than if early liquid nutrition is sufficient to meet or exceed their daily needs.

However, while it is true that feeding larger amounts of starter grain costs less than milk or milk powder as traditionally fed, dairymen that choose this approach are not capitalizing on the tremendous growth efficiency that young calves possess, if fed adequately, and they usually will see much higher morbidity and mortality in the young calves.

The typical dairy that follows a conventional approach feeds a milk replacer that contains 20-22 per cent protein and 15-20 per cent fat at the rate of about 1 lb of milk solids per day (DM basis). Under thermoneutral conditions, this level of milk feeding allows approximately 200 g of body weight gain per day for a 90 lb calf but during more stressful conditions such as cold, windy or wet weather, results in a state of semi-starvation.

Calves fed these traditional diets often suffer from significant weight loss or stunted growth. Additionally, there are often outbreaks of diarrhea at 7-10 days of age and preweaning respiratory disease that are caused (or at least worsened) by a compromised immune system and inadequate caloric and protein intake. A major complicating issue to the conventional approach is the low protein content of the calf starter.

The marginal level of calories serves to stimulate earlier and higher levels of starter grain consumption and can allow producers to wean calves at an earlier age, but these calves often crash afterward because of the low protein content. Remember, even if a conventionally reared calf increases its consumption of starter grain and is consuming the identical level of crude protein as a calf on a diet that provides a higher level of milk volume and/or solids, the digestibility of the two diets is usually not comparable. Milk and milk replacer is generally more digestible than the proteins commonly found in most calf starters.

Calves on a conventional diet usually have smaller frames and often have health issues that follow them through the remainder of the growing phase and into lactation. Also, with conventional rearing systems, typical age at first calving is usually between 25 and 28 months and the impact is a large delay in positive cash flow (milk production) and requires a greater number of youngstock to fill the gaps created by culling poor producing animals.

Intensive management programs have begun receiving a lot of attention in the last few years. These programs involve the feeding of rations that are higher in metabolizable protein without enough extra energy to promote fattening 2-7. During the milk feeding period, calves are provided with larger volumes of more nutrient dense milk or milk replacer. Typical formulations are 28 per cent protein and 18- 0 per cent fat and are fed at a rate of 0.3-0.37 lbs of milk solids/ liter with a total of 4-10 liters of fluid volume depending upon the size and age of the calf. Feeding higher levels of nutrients will allow 1.7 to 2.5 lb or more of body weight gain per day, depending on environmental conditions and volume of milk provided. Also, the higher level of nutrients can allow calves to withstand more environmental stressors without resulting in weight loss.

The downside of the approach is that the feed cost during the liquid feeding period is significantly higher and calves sometimes are slow to begin eating calf starter. The increased feed costs continue through the entire replacement rearing period. As calves grow and move through the various diet and pen changes, they are provided with rations that continue to be higher in metabolizable protein than comparable conventional rations and these larger heifers eat more feed per day due to their larger body size and higher growth rates.

However, these well-fed heifers usually experience the advantages of a reduction in both morbidity and mortality, reduced impact of cold weather stress, an earlier age at first service and first calving, and improved feed efficiency since total days on feed is reduced but rate of gain is increased.

In addition, there should be a reduction in the number of heifers required to enter the replacement stream since fewer animals are lost during the rearing process. One very impressive benefit that cannot go unmentioned is the higher levels of milk yield during the first and subsequent lactations that is the result of improved nutrition and management as heifers.

Results and Discussion

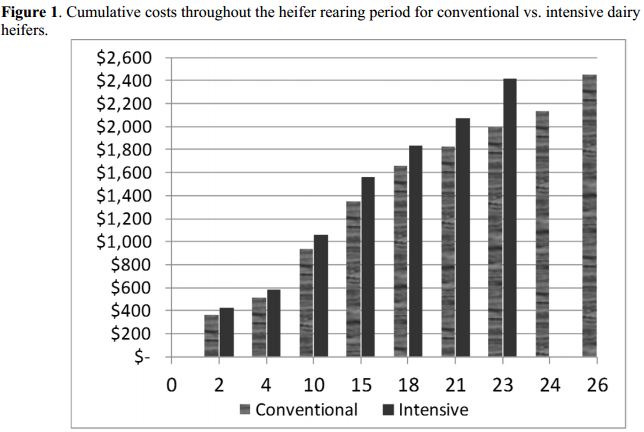

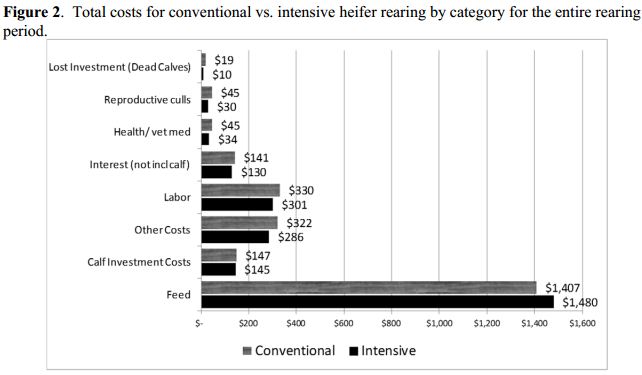

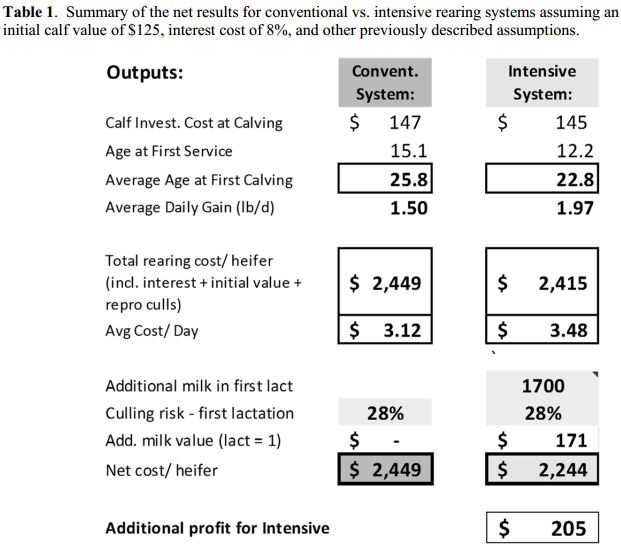

Throughout each growth stage, the intensive system costs more per day, as shown in Figures 1 and 2, but the conventional system results in a higher total cost per heifer due primarily to the longer feeding period. The total rearing cost is estimated to be $2449 and $2415 for conventional vs. intensive heifers, respectively. The $35 advantage for intensive rearing does not include the value of the extra milk predicted in the first lactation for the intensive heifers. After accounting for the delayed return for the extra milk production (after calving for first time), for the additional feed cost associated with the extra milk, and for the impact of culling during the first lactation, the net value per heifer is estimated to be $180 as shown in table 1.

Based on the assumptions used in this model, the intensive approach results in $73 higher feed costs, but results in savings in labor ($29), health and vet med costs ($11), interest costs ($10), reproductive cull costs of ($9), costs of dead or culled calves ($13), and housing costs ($36) for a net result of a “savings” of $35 per calf for the intensive program, not including the value of the additional milk. Addition of the predicted time-adjusted value of the extra milk results in a total economic advantage of $205 for the intensive program.

Within this model, attempts have been made to represent the true estimated costs and returns of each program as carefully as possible. As more systems implement the intensive heifer rearing approach, more data will be generated to help validate this model. Many people will likely be surprised at the total estimated cost of rearing heifers in either system, but this model reflects the current high feed costs that many have not considered over the entire rearing period. A key take home message from this work is that while the individual cost/d may be higher, capitalizing on improved growth efficiency that is possible with higher metabolizable protein rations, especially early in the growth and development of calves, results in a lower cumulative cost that is realized at calving.

Many people are skeptical of the projected increase in milk production that is attributed to the intensive program. However, the literature actually shows increased milk production not only in the first lactation, but also carrying over into the second lactation for heifers fed for intensive growth during the rearing period and this value is not captured by the model.

Even without the projected additional milk in the first lactation, the advantage is still tilted towards intensive rearing.

Another benefit not currently captured is the ability to either maintain fewer heifers in the replacement pipeline or to grow extra heifers for potential marketing benefits. By growing heifers faster and with reduced morbidity and mortality, fewer calves need to be placed each month in order to meet the required number for replacement each year. If additional heifers were maintained above the basic replacement needs, producers would have the luxury of either selling additional springing heifers or calving these animals and then culling more heavily from the lactating herd in order to make more rapid genetic progress. These additional marginal benefits were not considered in this version of the model and yet the advantage is still clearly in favor of intensive rearing vs. the more conventional approach.

The model presented in this paper and its results were based on a combination of published data and from data generated on a large commercial dairy that works with Dr. Corbett. This private dairy generated thousands of calf weight data points that were used to develop an intensive management growth curve. Use of this curve allowed for the prediction of average growth expectations using specific milk and grain feeding approaches. However, the results presented here are quite conservative for the intensive calf rearing approach. Since this early work, Dr. Corbett has further refined his feeding approach and is now feeding even larger volumes of more nutrient dense milk replacer and higher levels of protein in his heifer diets.

As a result, Holstein calves are averaging over 2.2 lbs of body weight gain per day, morbidity and mortality are substantially lower than reflected in the current model, and approximately 90 per cent of the calves have reached breeding weight and height by 11 months of age. Results such as these further increase the advantage of the intensive heifer rearing program. However, even with what some would consider to be an overly conservative approach to modeling the two programs, there should be no doubt to the economic advantage of the intensive approach to rearing dairy replacement heifers.