Winter Livestock Care:Calculating Extra Feed

Wind chill can be beaten with wind breaks, better quality forage and high starch feeds, writes Rory Lewandowski, Beef expert at Wayne County Extension, University of Ohio.The weather forecast is calling for some extended cold temperatures, writes Mr Lewandowski. Over the course of winter cold temperatures, wind chill, snow, freezing rain and mud are all possible.

All of these winter weather conditions can negatively impact livestock performance and increase the energy requirement of the animal.

All animals have a thermo neutral zone, that is, a range in temperature where the animal is most comfortable and is not under any temperature stress. This is the temperature range that is considered optimum for body maintenance, animal performance and health.

*

"The general rule of thumb is that energy intake must increase by 1 per cent for each degree of cold below the Lower Critical Temperature"

The lower boundary of this zone is referred to as the lower critical temperature (LCT). Livestock experience cold stress below the LCT. An increase in the metabolism of the animal, generally by shivering, in order to maintain body temperature is one method of dealing with cold stress.

This requires more energy, either from fat stores or more energy intake in the diet. The general rule of thumb is that energy intake must increase by 1 per cent for each degree of cold below the LCT.

As hair coat or wool thickness is increased, the LCT decreases. For example, in cattle, the LCT temperature for a summer hair coat or a wet hair coat is 59 degrees F. The LCT temperature for a winter hair coat is 32 degrees F and for a heavy winter coat it is 18 degrees F. The LCT for goats is generally considered as 32 degrees F, and for sheep the LCT is 50 degrees F if freshly shorn or 28 degrees F with 2.5 inches of fleece.

The livestock owner needs to realize that once an animal's coat is wet, regardless of how heavy it is, the lower critical temperature increases to that summer hair coat LCT. This is because hair coats lose their insulating ability when wet. Sheep are the exception, since wool has the ability to shed water and maintain its insulating properties.

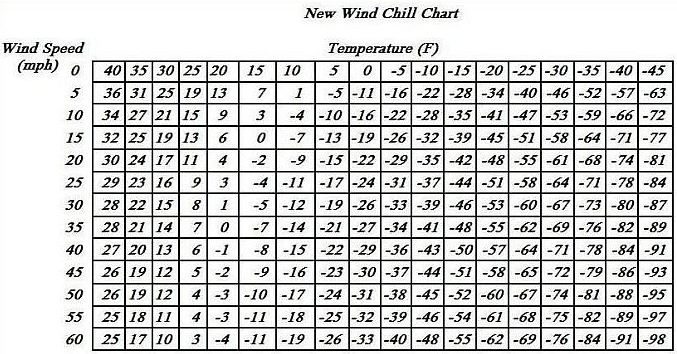

Wind speed produces wind chill and can further increase energy requirements for livestock when those values are below the LCT. The following wind chill table illustrates the effect of wind on decreasing the animal's LCT at various winter temperatures:

Mud can also reduce the insulating ability of the hair coat. The relationship between mud and its effect on energy requirements is not as well defined, but depending upon the depth of the mud and how much matting of the hair coat it causes, energy requirements could increase 7 to 30 per cent over dry conditions. In addition, there is research that suggests that mud may also be associated with decreased feed intake.

In systems where animals do not have regular access to a barn, livestock owners have several management options to help livestock cope with winter weather stresses, including:

- Provide windbreak protection to reduce the effects of wind chill on energy requirements.

- Increase access to better quality forage. Livestock can increase intake to some extent under cold conditions and if forage is of good quality, then energy intake is also increased. Grinding poorer quality forages to decrease particle size can allow more intake and increased digestibility.

- Limited feeding of corn, or use of a high energy, non-starch feedstuff.

- Move livestock out of muddy conditions or take steps to reduce the mud by utilizing a feeding pad.