Opportunities for Offal

Consumption of offal in the UK rose by 67 per cent between 2003 and 2008 and was valued at £62 million, writes TheCattleSite senior editor Chris Harris.The latest figures show consumption as stable between 2008 and 2010 at about 16,500 tonnes worth £40 million according to the latest figures from the Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board (AHDB).

While consumption of liver is just eight per cent of the market, in value terms is worth half the market, while consumption of kidney another offal products is slightly down.

However, Dr Phil Hadley the senior regional manager for the south of England for the English Beef and Lamb Executive told a conference on the use of the fifth quarter in Kenilworth in the UK that through marketing and direct intervention by products that would cost £2.2 million to dispose of could be turned into an income of £13.3 million - a £15.5 million turn around.

"A lot of material, particularly livers, is lost at the meat inspection stage because of parasitic infection," Dr Hadley told the Fifth Quarter: Go Green for More Profit conference.

"The loss is down to poor handling in the abattoir, particularly through gall bladder and pluck removal.

"It's the losses associated with farm practice that we need to get over and highlight costs to producers."

He said that much of the damage done to products that cause rejection and devalue the by products is down to liver fluke and Tenuicolis cysts (bladder worms) in cattle and sheep.

Dr Hadley said that in the UK 258,000 beef livers were lost to the food chain because of liver fluke at a cost of £258,000. In sheep 1.68 million livers were lost because of fluke and Tenuicolis cysts at a value of £1.59 million.

He said that animals with liver fluke do not put on weight and there is also a welfare issue that has to be addressed.

He said that if the cost productivity seen as a loss of 1kg a week with liver fluke, mortality and welfare is added to the equation, the impact is huge with an estimated cost of £25-30 per cattle case and a total cost of £7.74 million to the meat and agriculture industry.

Dr Hadley said there are two messages that have to be delivered to farmers - the necessity for treatment for liver fluke and also for the farmers to understand the financial impact it has.

However, he warned that the problems of persuading producers about the cost of liver fluke is made more difficult because of the lack of data although much of this date can be collated during the inspection procedure in the abattoir.

The inspection procedures themselves are also another cause of loss in the by-products market.

Dr Hadley said that the incisions that are made in the abattoir during inspection are spoiling the product and making it unacceptable on the food chain market.

"The incisions are damaging the product and making it unacceptable to the industry and for export in particular," he said.

"There is a great opportunity for the fifth quarter, but certainly there is significant loss at the abattoir and along the line.

"This needs to be addressed and the messages sent up and down the chain.

"There is a need to re-focus on this area and to exploit market opportunities where they exist. Communication, training and attention to detail are paramount," he said.

However, senior consultant with the MLC, Christine Walsh, said that to be able to exploit the potential of the fifth quarter many meat processors and abattoirs would have to update the operations of their gut room.

She said that many companies were losing up to £4,000 a week by sending potentially edible offal into bins for specified risk material.

"We are still just looking at the liver, kidneys, tongue, heart skirt and casings as potential for consumption and we are not looking at other products that can be used," said Ms Walsh.

At present the meat and offal market is divided into edible products which are largely the muscle meat, edible co-products such as fatty tissues bones and the edible gelatine and collagen used for casings.

Following these products, there are the by-products.

These are Category 3 products that are found fit but are not intended for human consumption, Category 2 products such as fallen animals, animals that fail tests at post mortem or contain residues or are soiled and then there are Category 1 products that are TSE positive products and SRM.

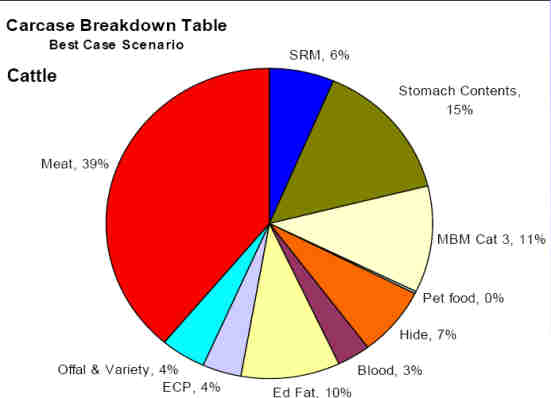

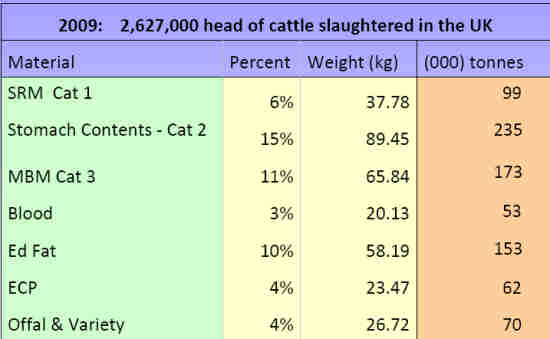

She said that a survey conducted in 2006 in Scotland found that 26 per cent of the carcase was going into Category 1 (SRM) products costing the industry £80 per tonne or £12.62 per animal.

She said that in small animals in particular most of the by-products were going in to Category 1.

However, she said that if the products and carcase are examined just six per cent is not fit for consumption or further use.

Cattle

"We can find markets even for the stomach contents," she said total.

Ms Walsh said that the challenge is to move products up the chain into areas where they can be used and marketed.

She said the industry needs to collect better data to measure the yield from the offal.

At present, the industry is only harvesting the key products and it is not paying attention to quality issues because there is a shortage of skills and a lack of management knowledge Ms Walsh said.

The way the by products are harvested, handled, chilled and stored is all important to maintaining profit.

She added that there are also concerns about the way that the by products are inspected as the methods are often too intrusive and damage the quality of the product for further marketing.

She said that making more out of the by products will help to reduce the carbon footprint and increase yield and price and the industry has to deliver what the market wants and in a condition that is saleable.