Controlling Worms to Improve Milk Yield

The stomach worm (Ostertagia ostertagi) is the most commonly identified worm in dairy cows.However, although over 90 per cent of animals can be infected, they rarely show overt clinical signs. This means that despite the reduction in appetite, fertility and herd productivity associated with these worms, they are often not perceived as a high profile herd health issue.

Worming: The Good Times

Dr Philippe Camuset has over 30 years’ experience as a cattle veterinarian in a mixed practice in Normandy, France; during that time he has become an expert in parasitology.

His experience has led him to develop a very pro-active approach to worming among his dairy clients, based on data from individual farms. For more than 10 years he has been conducting audits among his dairy clients and using the results to open an active dialogue with farmers and to develop a dynamic, structured approach to worming together.

“Farmers think that de-worming cattle is very easy to do and is effective at any time,” he explains. “I have to convince them that there is a best time to dose their animals.

“Many vets are afraid of the management of parasites, but this approach makes the discussion very comfortable for the vet with little danger of failure, as they are using data.”

He shows his farmers data from an audit of their own herd in the form of tables and uses these as the basis for a discussion of the potential impact and the most appropriate form of action throughout the year.

“This convinces them of the need to de-worm and they follow my advice on when and how to do it.”

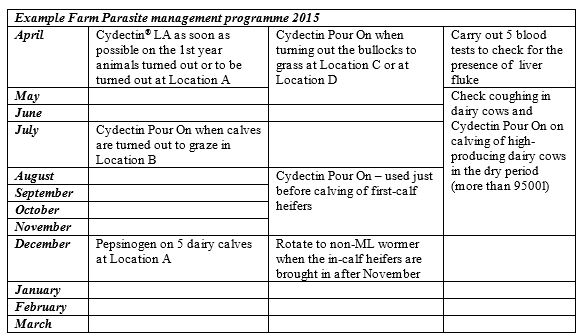

The detailed schedule varies from herd to herd depending on its individual needs. The following table is an example of a summary developed for one of his clients based on the current assessment of his herd:

He often suggests that calves are wormed just before turn out, and that heifers and high yield animals are wormed at calving in order to reduce the impact of infestation during lactation. This approach has allowed anthelmintics to be used in a more preventative way and has produced benefits for his dairy clients:

“Cows are getting pregnant earlier and they look better, and both dictyocaulosis (lungworm) and ODR (Optical Density Ratio – for Ostertagia ostertagi antibodies) have decreased,” he says.

For the last seven years Dr Camuset has been President of the parasitology group of the SNGTV (the national technical organisation for veterinarians in France). He is a firm believer in the benefits of a structured worming programme that enables the effective use of anthelmintics, but without using these treatments any more than is necessary.

He has found that generating data from the individual herd and discussing this with his clients is the best way to motivate farmers to follow a structured and sustainable de-worming programme:

“The two sets of data to discuss with farmers are the level of clinical episodes relating to parasites, and a systematic laboratory assessment of the type and level of parasites,” he says.

“I think it is also worth convincing farmers that a series of tests, such as microscopy, serology, ODR, pepsinogen and coproscopy, are worth doing because they provide a picture of which parasites are present in the herd and at what levels. You can then speak to the farmer about the potential impact on health and production, and this will motivate them to follow a recommended programme.

According to Dr Camuset, duration of action and withdrawal times are key factors when deciding which anthelmintic to use at a given time:

“One of the times I suggest for routine de-worming is at the end of the dry period just before calving. At this time I suggest moxidectin because it lasts a bit longer, so the benefits are greater,” he says.

Published studies have confirmed that treating animals with a pour-on wormer in the late dry period before the start of lactation can increase milk yield from between 0.54kg and 1.24kg per day [Yazwinski et al 1999, Rock & Clymer 2002, Murphy 1998]. That is equivalent to 183 litres per cow based on a 305-day lactation.

“If worming is done during lactation as a strategic approach according to epidemiology, then I would suggest a product that has a zero milk withdrawal period, so there is no loss of production,” Dr Camuset concludes.