Joel Salatin of Polyface Farms Reveals the Secrets of ‘Beyond Organic’ Farming

Polyface Farm, an alternative “beyond organic” operation is situated in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley. Its operator, Joel Salatin, has been called by TIME magazine “the world’s most innovative farmer” and “the high priest of pasture and the most eclectic thinker from Virginia since US President Thomas Jefferson”, writes John Wilkes.When it was purchased 55 years ago, Polyface Farm was said to be “the most worn-out, eroded and abused farm in the area”. This multi-generational family holding now generates $1.83 million (£1.5 million) in annual farm sales. Its goal, according to its visionary owner, Joel Salatin, is to raise animals that yield integrity edible food – which for him means without exposure to any chemical or fertiliser.

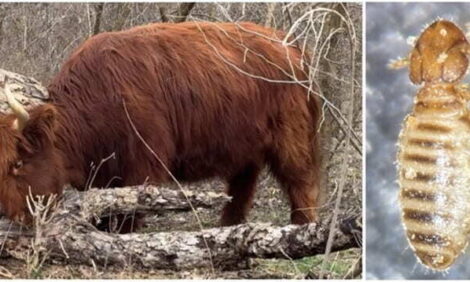

Joel Salatin amongst the beef herd at Polyface Farm

Farm policy deliberately avoids sales targets, marketing and business plans. The belief is that if food is good enough, it will sell and generate sales. Beef is the largest contributor to Polyface’s revenues and it has the greatest impact on the farm’s holistic pasturing strategy.

Polyface Farm comprises 72ha of open grazing and 190ha of woodland. An additional 404ha of grazing is rented across ten properties with the largest at 145ha and the smallest at 0.6ha. All livestock – cattle, table chickens, laying hens, turkeys and rabbits – enjoy full exposure to forage.

Farming is uncomplicated, and complemented by basic, no-frills buildings. Only the bare essentials in farm equipment can be found on-site: manure spreaders, front-end loaders, a wood chipper to create cattle bedding from homegrown timber, stock trailers and feed buggies that deliver feed to livestock.

“An average American farm takes $4 worth of depreciable capital infrastructure for buildings and machinery to turn $1 of gross sales,” says Mr Salatin. “Polyface needs just 50 cents – an 800 percent difference in capital intensity.” The farm invests that difference in 20 members of staff. “We’d rather have more eyes to the acre, detailed management and improved staff skill levels,” explains Mr Salatin.

Outdoor table birds aid soil fertility under the Appalachian Mountains at Polyface Farm

Cattle graze intensely on fresh ground every day. Mr Salatin defines “holistic” as a mixture of science and art form. Daily forage allocations are dependent on the time of year, availability and herd size. The extensive outdoor meat and egg poultry enterprise help soil fertility.

Cattle number 900 head at peak. The breeding herd numbers 150 cows; the remainder consists of bulls, juvenile cattle, 150 purchased stocker calves, finishers and replacements. Cattle are handpicked every two weeks for slaughter. “Nothing goes to the stockyard,” says Mr Salatin. “Cull bulls and cull cows are turned into ground beef or hot dogs; we salvage product.”

Beef from 300 prime cattle sell retail direct. Polyface, Inc customers include 50 restaurants, a farmers’ market, five retail outlets and 6,000 members in their innovative Metropolitan Buying Club programme. This scheme combines online marketing with community-based interaction. It offers group delivery drop-offs at locations up to three-and-a-half hours away. Participating members need to order $1,000 (£770) minimum to take advantage of this strictly local delivery service.

When building his beef herd, Mr Salatin applied a radical approach. He kept it closed to outside genetics to create a homegrown “breed and feed” composite to suit the conditions. For ten to 12 years linebreeding has been in operation from a mixed gene pool that initially included Black Angus, then Red Angus, Shorthorn, Hereford smatterings of South Poll and even Texas Longhorn.

Cow longevity, a critical trait, is purposely bred. Mr Salatin says: “It influences taste, meat quality, docility, maternal instincts fertility and health.”

The advantage of tight breeding is free potency and predictability; its disadvantage is that over time it accentuates every weakness. To follow this path requires ruthless culling. Any assistance given to a heifer at calving for any reason means she is removed after weaning. This “two steps forward and one step back” approach makes it hard to build up cow numbers if cull rates are high.

Tightly controlled grazing in 38C summer temperatures with limited shade makes skin colour a consideration. Black Angus does not do well in heat. Red, tan, beige and grey cattle stay cooler and are more comfortable during hot summers.

Finishing cattle at Polyface are moved everyday along with mobile shade

Pursuing these traits produces compact, thrifty, heat-tolerant, easy-care cows that average at around 1,000 lbs (450kg) in weight and that grow calves quickly.

The herd calves outdoors during a 60-day period from early April to June. In 2015, Polyface Farm adopted a different strategy to weaning. Calves remained on their dams through winter to within a month of calving before joining 150 autumn purchased stocker (store) calves. Mr Salatin says he’s pleased with the results: “We’re sold on it. Although cows lost some body condition, the calves were fabulous. Cows dried themselves off naturally. Weaning was totally stress free and with a low incidence of mastitis.” High-quality forage ensured cows gained condition in a month and calved down without the need for additional hand feed.

A flush of cool-season grasses and clovers in the autumn supplies ample winter forage cover. Even when frosted it provides more nutrition than hay. Polyface feed cows hay for 40 days during winter. This triples production per cow in comparison with traditional regimes in operation in neighbouring farms, where average hay feed is 120 days.

Winter finishing cattle are open housed once the stockpile of allocated forage has been consumed. No grains are fed. High-quality ‘grain hay’, mostly second-cut young, leafy material and free-access minerals, is used.

Finishing cattle at Polyface Farm

Slaughter before 24 months is avoided, with optimum slaughter at 26 to 32 months. Steers yield a 250-275kg carcass and heifers a 237kg carcass.

Six years ago, when the local slaughterhouse was at risk of closure, Polyface, Inc invested and it now has a 40 percent share to safeguard production. The facility is currently undergoing a $500,000 (£400,000) upgrade that includes additional manufacturing space.

Moving forward, Joel Salatin believes “value-add” is gaining momentum. He says: ‘The reality is people now want edible convenience food. Microwavable meals, jerky, pies, stocks, charcuterie – that is the growth area in our movement. We produce great cuts of meat and whole free-range chicken, but we’ve plateaued; heat-and-eat is the next big thing.”

Joel Salatin will be in the UK on Wednesday 23 November for an evening seminar and panel discussion on sustainably managed livestock in future UK food systems. The Sustainable Food Trust and the Cabot Institute will co-host ‘The role of livestock in future farming systems’ at the University of Bristol.

John Wilkes

Freelance journalist

John Wilkes is a former UK sheep and beef producer now living in Washington DC. His experience in both the UK and US gives him a unique perspective on livestock and food production.

Nowadays he writes and consults about livestock and agriculture. He also hosts a broadcast radio programme called The Whole Shebang on Heritage Radio Network from Brooklyn, New York.

John is a board member of The Livestock Conservancy in the US and a member of The American Sheep Industry Association.